TRUSTED BUYERS OF AMERICAN ESTATE STONEWARE AND WEEKLY STONEWARE AUCTION

TRUSTED BUYERS OF AMERICAN ESTATE STONEWARE AND WEEKLY STONEWARE AUCTION

CAPTAIN JOHN NORTON AND THE LEGENDS OF STONEWARE

Goshen, Connecticut

The Norton Family stoneware history is very well documented. The family's ware is one of the first encounters new collectors and enthusiasts have, when beginning to look into American stoneware. The museum in Bennington, Vermont has an extensive collection of Norton pieces, as do museums in New York State and around the country. If you haven't visited the Bennington Museum it is perhaps the most extraordinary collection of one family's work in one place in the United States.

The vessel pictured above, is a red ware cup shaped vase, donated to the museum by the Pratt family. It is dated to the 1810 to 1820 time period and is attributed to Captain John Norton's original kiln in Bennington. The provenance is strong here, it was willed to, then owned by, Mrs. Luman S. Norton Pratt, and was donated by her, directly to the museum. For those who study stoneware and the makers, this is a characteristically odd piece of ware from the patriarch of the Norton clan. To begin with, we all expect to see stoneware, not red ware, but the facts are that Captain Norton was first a red ware maker in Vermont, and did not have a ready supply of stoneware clay on which to use. So red clay it was.

Perhaps I am getting ahead myself so let's start at the beginning, and the beginning is not in Bennington, Vermont, it's in Goshen, Connecticut. Goshen is about an hour north of the southern coast of Connecticut and New Haven, home of Yale University. Norton was originally from Goshen and was born in 1758. There was a pottery operating in Goshen during this period owned by John Kettle and one school of history supposes Norton learned his trade there. The Kettle family later become legends in their own right in Charlestown, a story for another day, but it's astounding that these two legendary families actually may have shared history. By 1784, Norton, now a Revolutionary War ranked Captain with family, had found his way to Williamstown, Massachusetts, then called Williamson, on his way to Bennington. Yet another historian has Norton making/learning stoneware production there, for a short period. These two entries into the Norton family history are without documentation and are based on information passed on by generations which came after. Both very logical though.

As a side notation, its also quite possible that Norton and Norton's family in Goshen had known the Fenton family of New Haven, given the close proximity of the towns. These Fentons are the same legendary Fenton's we will encounter later in this story.

FARMING AND POTTING IN BENNINGTON, VERMONT

TWO GREAT OCCUPATIONS IN ONE GREAT MAN

So, as the history goes, Norton with family in tow, reaches Bennington, Vermont, sometime in the 1790's. Norton purchases land there and begins, as most did in the 1790's, to farm.

A perspective look at the times may give us all a grasp of respect for the people who lived them. No grocery stores, no pharmacies, no nice restaurants...it was primitive, really primitive, by today's standards. If you wanted to have vegetables...you grew them... meat... you raised it...game... you shot it. So farming WAS the norm. So many of our early American Potters were also farmers. The cycle was to farm all summer, bring in the harvest in the fall, throw pottery all winter, then fire the kiln up on the first days of warmer weather. Kilns needed temperature stability and warmer weather to fire the pottery well, so it was really a dice roll.

Norton's kiln was built, we are almost positive, with the intent on selling some pottery, once it was fired. In the early years it was red ware or earthenware. The clay was found locally the wood chopped out of the slab of land you wanted to make into a pasture and the glazes lead based and sometimes smelted out of local rock. Again...PRIMITIVE.

Norton builds his kiln in 1793 on his farm. The site has since been excavated to the immense joy of the curators at Bennington Museum. Norton had a son with his wife Lucretia, named Luman, who was about eleven when the kiln was erected and was soon learning the trade. Along side him, a nephew of Mrs. Norton, Norman Judd, also worked at the kiln, starting around the age of fifteen. The three made firebrick, jugs, crocks and plates all from the red clay.

The jug pictured, was one made for Miss Omindia Gerry of Bennington aged 10 years. It was passed from generation to generation until donated to Bennington Museum by the Gerry family. The jug is the oldest documented piece of Bennington pottery known and was made at the original kiln site on Captain Norton's farm by a potter who worked for the Norton's.

The jug has an extraordinary look and was decorated with most likely a lead based glaze which turned out was unhealthy to smell when baked, when eaten off of or drunk out of. It's really a beautiful jug to look at in this authors eye and perhaps a prelim to what was to come.

ALONG COMES STONEWARE!

JONATHAN FENTON AND THE NORTONS

In as early as 1810, Captain John Norton and his tradesmen, now four or five in total, began making stoneware pottery. What's the big deal here? Clay is clay....right? No! Stoneware clay was named stoneware for a really good reason. It wears like stone! The red clay was porous and somewhat brittle. It broke easily and chipped even easier than that. The stoneware was really durable and held up much better and would hold liquids for extended periods of time, something red ware could not do well.

The likelihood that Norton was making stoneware at this moment of time, all but giving up most of the red ware manufacturing he was so trained at making, was no surprise. Jonathan Fenton and his family arrived in East Dorset, just a few miles from Norton's farm at the same time Norton began making stoneware, about 1810. Fenton's family had been owners of a stoneware pottery in New haven, Connecticut for years and had a generous and active supply of good clean stoneware clay. Fenton had been working in his own pottery in Boston and knew he could get the good clay, by way of barge up the Hudson River to Troy, New York. Fenton who had been in Boston with Frederick Carpenter on Lynn St. making stoneware, was a valued friend and great business contact for the Norton's. Fenton began making his own stoneware in East Dorsett and the two families quickly supported each other and there are records of them sending wagons to Troy for shipments. Later the families would intermarry and they became family and eventually officially business partners as well. The overall thought is that Fenton came to Bennington BECAUSE of Norton and that there was a plan in mind to collaborate. So the introduction of a source of stoneware clay was an important step in the foundation of Norton stoneware.

Pictured above are the potters of Bennington. The top hat is Edward. 1871. Notice the use of very young boys. Second from the left , back row is also a member of the Norton family.

A CENTURY OF FINE POTTERY

GENERATIONS COME WITH MORE PERFECTIONS

The advent of stoneware was a windfall for the farmer Norton and his family. The ware was bought by everyone around and the business grew. Then there were the sons, cousins and nephews that followed. It's all part of the rich history that began with Captain Norton's humble farm in Bennington just after the American Revolution. 100 years of a family gift!

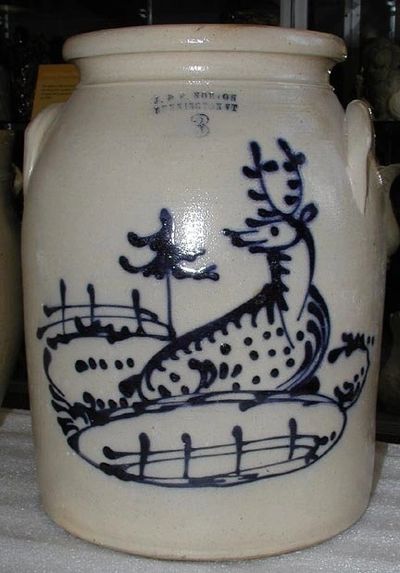

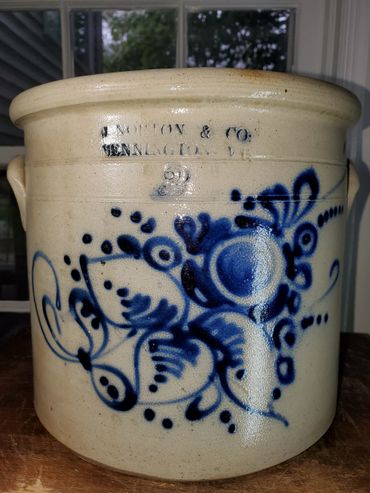

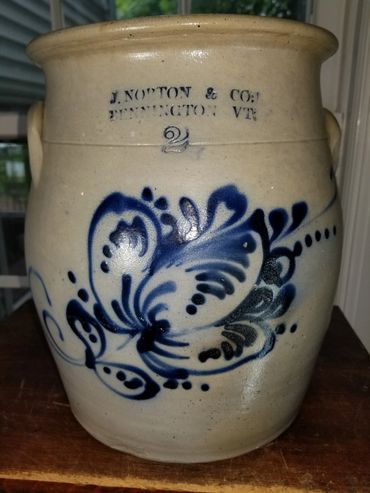

There were many who worked very hard for this pottery to succeed. Most will go unnamed for the use of time and space. There would be Luman the first with a flair, followed by his son Julius the masterful businessman and potter. Then Edward and Luman Preston Norton and the figural pieces with deer and farmhouses and more. Finally, it was Edward Lincoln Norton who saw the end of the stoneware era in the dawn of the Industrial Revolution of the 1890's. It was almost never ending, but it did. The extent that which these artisans stretched the envelope of combining creative and utilitarian pottery which then became our American heritage, is astounding.

Plan a visit to Bennington and see what hard work and dedication can do. Just amazing. American grit!

SOME PICTURES OF NORTON STONEWARE, AMERICAN STONEWARE COLLECTORS, HAS SOLD OR AUCTIONED

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.